Recent Posts

Subscribe

Sign up to get update about us. Don't be hasitate your email is safe.

Supreme Court

Supreme Court

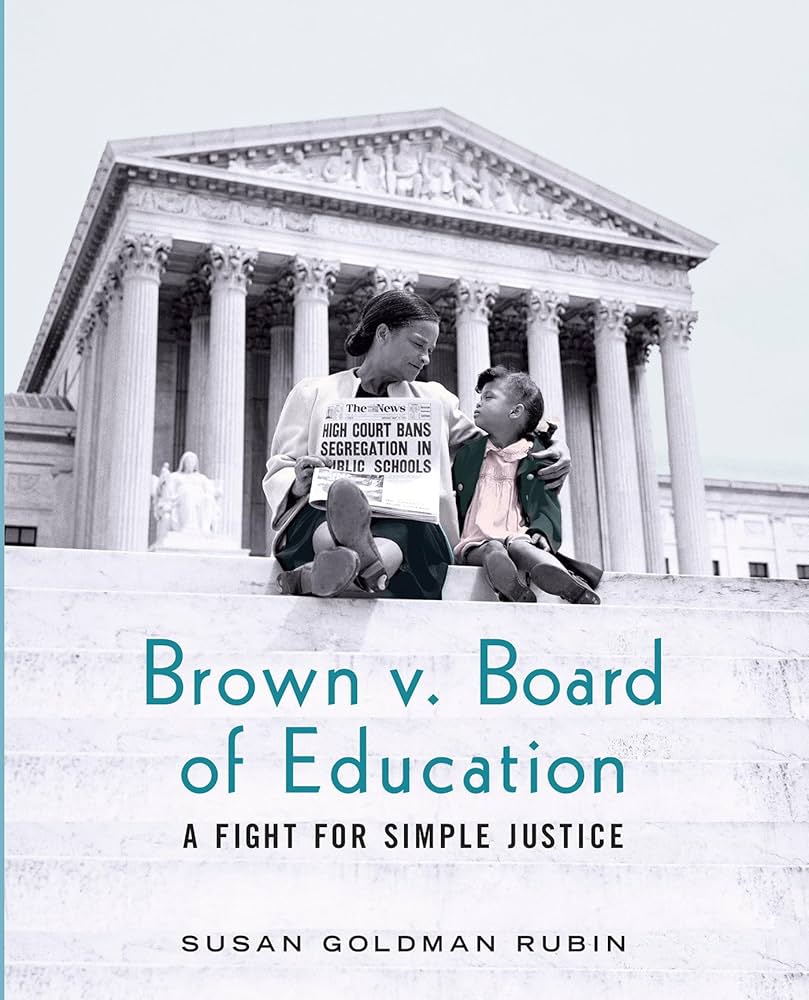

In 1954, the Supreme Court declared in Brown v. Board of Education that racial segregation in public schools was unconstitutional. The decision itself was transformative, and equally as remarkable is the fact that it was unanimous. This harmony was no accident — and it very nearly didn’t come to fruition.

The Court originally heard arguments in the five public school segregation cases packaged under Brown in 1952 under the leadership of Chief Justice Fred Vinson, who was reluctant to overturn the deeply entrenched “separate but equal” doctrine. When Vinson’s sudden death led to the appointment of charismatic politician Earl Warren, a staunch advocate for desegregation, the fate of the case took a turn.

Warren, aware that a divided Court would give segregationists ammunition to fight any order to integrate schools, spent months swaying each of his fellow justices to his side. In particular, he had multiple lunches aiming to win over Justice Stanley Reed, who initially contemplated dissenting for fear that a decision ending segregation would overstep the bounds of judicial power.

Warren, aware that a divided Court would give segregationists ammunition to fight any order to integrate schools, spent months swaying each of his fellow justices to his side. In particular, he had multiple lunches aiming to win over Justice Stanley Reed, who initially contemplated dissenting for fear that a decision ending segregation would overstep the bounds of judicial power.

After months of top-secret deliberations among the justices, Warren crafted an opinion that he said must be short, readable, and nonaccusatory — the best way to minimize disagreements among the members of the Court as well as the public. Not only were Black and white public schools fundamentally unequal, Warren wrote, but forcing Black children to attend inferior schools damaged their self-esteem and was a violation of the 14th Amendment’s Equal Protection Clause.

Justice Robert Jackson, who had planned to author a concurrence disagreeing with certain elements of the majority opinion, read the draft while recovering from a major heart attack in the hospital and declared it a “master mark.” Just as Warren intended, his simple yet powerful words convinced all the justices to speak against racially segregated public education in one voice.

Of course, the civil rights triumph in Brown is not only a credit to Chief Justice Warren’s persuasive efforts. It was the culmination of the NAACP’s decades-long strategy to dismantle the legal foundation of segregation. Thurgood Marshall, who led the NAACP’s Legal Defense Fund, argued for the winning side and went on to become the first on the Supreme Court.

Nevertheless, segregationists mounted a campaign of massive resistance against integration. The Court issued two more decisions ordering the implementation of Brown nationwide , but states exploited the ambiguous language to delay compliance for decades.